help(median)Functions

Most of the things we will do when using R will be done using functions. We can think of a function as an (often) elaborate sequence of simple operations. As such, they can involve more than two objects. However, functions are not only more elaborate than operations using a binary operator; they are also more flexible, because we can modify what a function does or how it does it via its additional function arguments.

Consider, for example the function matrix() we used previously. It is flexible because the function arguments nrow and ncol allow us to create matrices of arbitrary size.

The basic setup of R functions

All R function share the same set-up. The function has a unique name by which we can call it, and it has a number of function arguments that we need to specify in parentheses following the function name when calling the function.

Function arguments can be objects that we would like to feed to the function or parameters of the function that influence what the function does. Some of a function’s arguments are required arguments, that is, if we do not specify these arguments, the functions won’t run. Instead, R will complain by printing an error message telling us that we did not specify a required function argument.

A function may also entail optional function arguments. Technically, these arguments are also required, but the person who wrote the function defined default values for the arguments. If a function argument has a default value, we do not need to specify it in order for the function to run. The function will simply run as if we had entered the respective argument’s default value manually.

Occasionally, we might come across functions that have no arguments at all. These functions are quite rare. We can can them by writing nothing in the parentheses following the function’s name.

The most useful function in R - help

All functions in R are documented in order to help users understand what the function does, what its arguments are and what they do. We can ask R to show us the documentation using the function help(). If we call this function and feed it the name of an R function as a function argument, R will display the documentation in the help tab of the utility & help section (bottom right of RStudio’s interface).

Note that the function help() will accept the function name both if we enter it as is or if we enter it as a character string (i.e., we write it in quotation marks).

As an alternative to calling the function’s name in regular R syntax, we can type the functions name in the search bar of the help tab.If we use this way to learn about a function, we do not need quotation marks.

Once we call the help function, R will show us the documentation of an existing R function or a group of related functions. R will generally display a lot of information. What information is displayed exactly depends on the function.

The following information will be shown for all functions:

- the name of the function

- what R package it is from

- a description of the the function does

- how to call the function (usage)

- the functions’ arguments

- a description of the type and format of the function’s output (value)

- functioning R code showing examples of how the function can be used

There may be additional information for some functions such as: - a description of the maths or logic underlying the function (details) - additional information of potential interest to the user (note) - references to literature the literature the function is based on - links to related functions (see also)

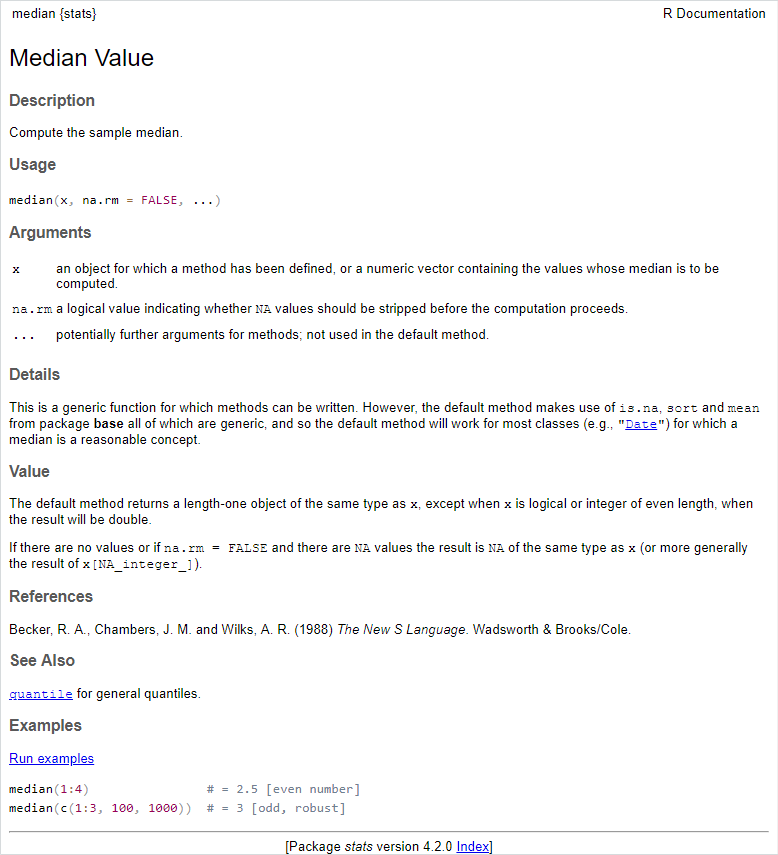

Let’s look at an example by asking R to show us the documentation for the function median() using R syntax.

R will now show us the following in the help tab.

Let’s first look at the description. Unsurprisingly, it states that this function computes the sample median.

One of most relevant sections of the documentation is the function’s usage. As we can see, the function median() has two function arguments, x and na.rm. The second argument, na.rm has a default value, indicated by the equal sign and a specific value (FALSE) to its right. If we do not specify na.rm, R will use the value FALSE as a default. Since the argument x has no default, we must specify it. Otherwise, the function won’t run.

The other highly relevant section is the arguments section. It tells us what the function arguments do and values are acceptable for each of the two function arguments. The argument x must be a numeric vector (we can ignore the first part of the sentence referring quite obscurely to ‘an object for which a method has been defined’). This is the set of numbers for which we will compute the median. The second function argument, na.rm, defines how missing values (represented by NA, meaning “not available”) should be handled. The function will not work when our numeric vector x contains at least one NA value. By setting na.rm to TRUE, we can tell R to remove the NA values prior to computing the median.

Finally, let’s inspect the value section. From what the function is supposed to do, we would expect it to return a single numeric value. The documentation tells us that this value can be a double type value when the vector is of even length (in this case, the median is the mean of the two centre most values of x). It also informs us that the output of the function will be NA if x is either an empty vector of if x contains NA values while na.rm is set to FALSE.

At the top left of the documentation, R states in braces following the function’s name which R package it stems from. In case of the function median(), the package it belongs to is called stats. This package along with base is built into core R.

Caveat: If a function does not belong to one of R’s built-in packages, R’s help() will not know the function unless the respective package is loaded (see the section on installing and loading additional packages for more information).

Finding functions if their name is unknown

Sometimes, we might be looking for a function to perform a specific operation, but we do not know whether R has such a function and, if so, how it is called in R. In such situations, we can make use of the search bar on the top right of the help tab. If we input the term we are interested in there, R will return a list of related functions in the help tab.

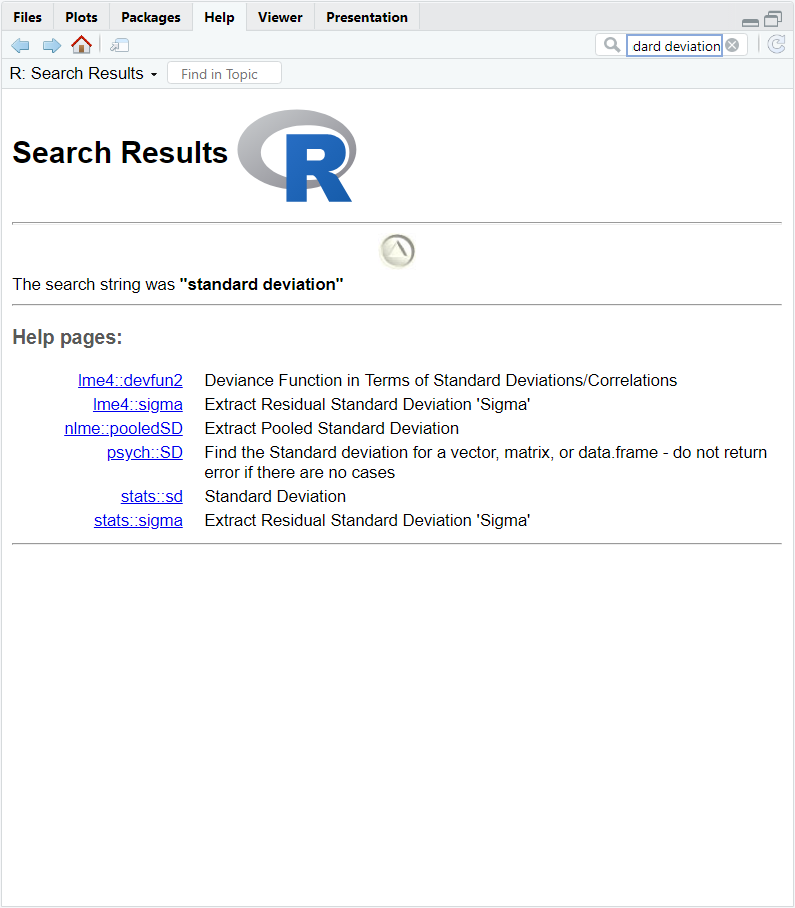

Let’s assume, for example, that we are looking for a function that computes the standard deviation of a numeric vector. Entering the term “standard deviation” in the search bar, yields the following output:

As we can see, R links to several help pages, each of which contains the documentation for a function that R thinks to relate to our search term. R displays the results of the search in a special format, namely package_name::function_name. For example, the first result of the search is the function devfun2() of the package lme4. Klicking on any of the links our search returned is equivalent to using the help() function for the respective function.

Note that unlike the regular help() function, using the search bar is not restricted to currently loaded R packages. Any package that is installed on the computer will be included in the search. This handy feature is designed to maximize the chance of finding the function we are looking for.

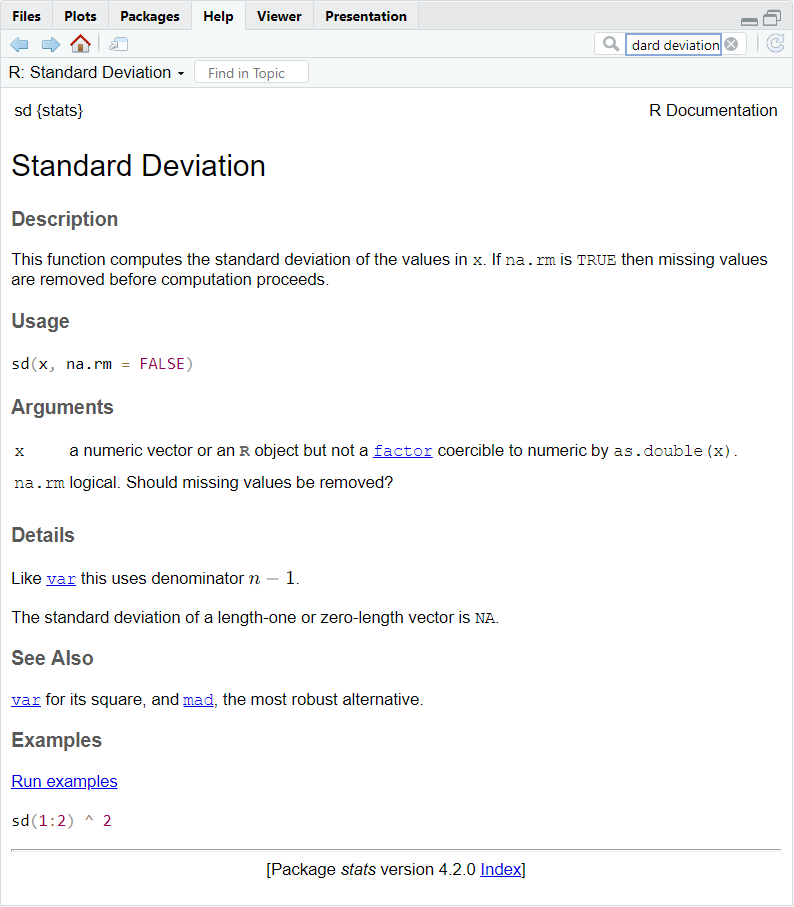

In the example above, we can see that there is a function called sd() in the stats package that is part of basic R. The brief description of this function looks promising enough to warrant klicking on the function’s name. The documentation for the function that R now displays confirms that this is the function we are looking for (see below).

As we can see from the documentations usage and arguments sections, the function sd() requires a numeric vector x as a function argument. It has a second optional argument we are already familiar with, namely na.rm, which allows us to exclude NA values prior to computing the standard deviation.

Let’s have a look at the details section of the function sd(). This section contains an important piece of information, namely that the function uses the denominator \(n-1\). What this means is that the function sd() computes an unbiased estimate of the population standard deviation by multiplying the (uncorrected) sample variance by \(\frac{n}{n-1}\) prior to taking its square root.

An alternative to using the search bar of the help tab is to use R code to search for functions. We can do so using a special operator ?? followed by the term we are searching for. If our term consists of more than one word, we need to put it in quotation marks (putting a single word in quotation marks won’t do any harm).

The syntax looks like this:

??"standard deviation"We can verify that searching for our term of interest using R syntax yields the same results in the help tab.

Caveat: There is one situation in which using the search bar of the help tab and using the operator ?? will yield different results. If the search term matches the name of an R function, either from base R or from a currently loaded R package, the help tab will always display the documentation for that function instead of providing us with a list of potentially relevant functions. Using the ?? operator will always display the list of results.

If our search for the desired function is not successful, Google (or any non-evil alternative search engine) is our friend. R has a very active and supportive community, and there are extensive resources for R users on-line.

Combining several functions

We will frequently find ourselves in situations, in which the operations we want to perform require calling not just one function but a sequence of functions.

Consider, for example, a case, in which we want to create a list type object that contains descriptive statistics for two variables we observed. The first element of that list will contain the variables’ means while the second will contain their variance-covariance matrix.

Creating the first element of that list is simple as it requires only computing the means whereas creating th 2x2 matrix requires computing the variances of the two variables as well as their covariance and then putting them in a matrix format.

The first way to go about this is to write R code such that we call each function separately and save its output as a new object. We then use this object as a function argument in the next function we need to call. Another possibility is to use a function call as the argument for the next function. Lets have a look at these two options.

Calling functions separately.

v1 = c(2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13) # data for variable 1

v2 = c(1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13) # data for variable 2

# compute means for v1 and v2 using the function 'mean'

mean1 = mean(v1)

mean2 = mean(v2)

# create a vector of the means using the function 'c'

mean_vector = c(mean1, mean2)

# compute variances using the function 'var'

var1 = var(v1)

var2 = var(v2)

# compute the covariance using the function 'cov'

cov12 = cov(v1, v2)

# create the variance-covariance matrix using the

# functions 'matrix' and 'c'

vc_vector = c(var1, cov12, cov12, var2)

vc_mat = matrix(vc_vector, nrow = 2)

# now create the list using the function 'list'

my_list = list(means = mean_vector,

var_cov_matrix = vc_mat)We can now have a look at the object we crated by calling the name of our newly defined list.

my_list$means

[1] 7.142857 4.714286

$var_cov_matrix

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 16.80952 17.04762

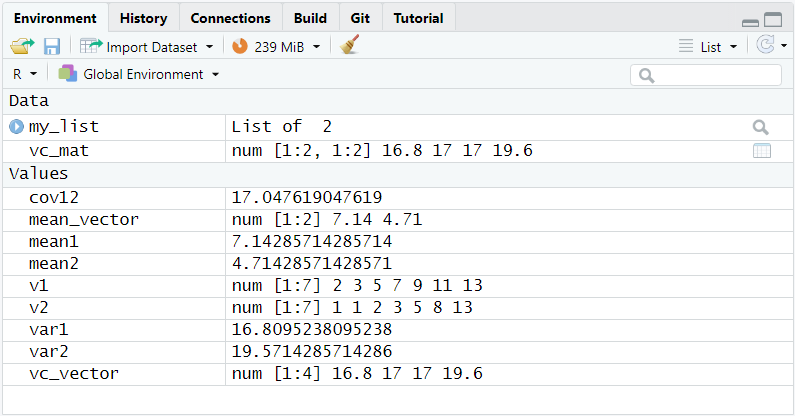

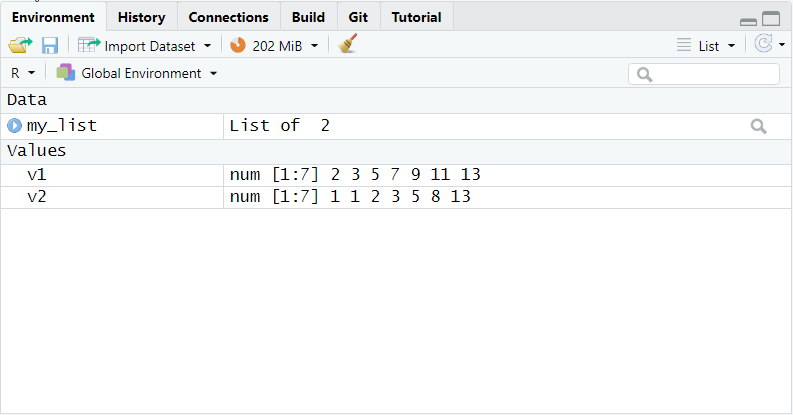

[2,] 17.04762 19.57143As we can see, the objects looks exactly as it should, and it contains the information we want it to contain. There is, however, a drawback to the piece-by-piece approach, we took in creating the list. It becomes apparent when we look at the Environment tab of the Memory section (top right).

Since we defined the output of each function as an object of its own, our Environment contains not only the list we wanted to create, but also ten additional objects.Two of them are the original data, which we may want to keep, but the other eight objects are no longer required. Eight superfluous objects may not sound too much, but if we work on more complex tasks in R, the number of superfluous objects may increase rapidly.

One solution to solve the problem is to clean up afterwards using the function rm(). This function takes an arbitrary number of R objects as function arguments. It removes all listed arguments from the Environment. Here is what the code looks like in our example.

rm(mean1, mean2, mean_vector,

var1, var2, cov12,

vc_vector, vc_mat)After we run this code, the Environment looks much tidier. It now contains only the original data vectors v1 and v2 as well as the list containing the descriptive statistics.

Calling multiple functions in one go

An alternative to calling each function separately and defining interim objects is to use function calls as arguments for other functions. In theory, it is possible to write one(very long) line of code to create our list of descriptive statistics from the two data vectors v1 and v2. Here is what the code would look like.

v1 = c(2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13) # data for variable 1

v2 = c(1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13) # data for variable 2

# create the list using the function 'list'

my_list = list(

# create the first element of the list using the

# functions 'c' and 'mean'

means = c(mean(v1), mean(v2)),

# create the second element using the functions

# 'matrix', 'c', 'var', and 'cov'

var_cov_matrix = matrix(

c(var(v1), cov(v1, v2), cov(v1, v2), var(v2)),

nrow = 2)

)In the example above, the R code is spread out between multiple lines for the purpose of better readability. We could have actually put it all into one line. If we now look at the Environment, we will only see the two original data vectors and the list we created. No interim objects were created, and there is not need to clean up afterwards.

Note also how the code starts with the last step of the step-by-step approach. That is, if we use function calls as arguments for other functions, we need to think from the end to the start.

One downside of writing code containing convoluted function calls is that the code may become more difficult to parse for others or even for ourselves (especially if we revisit a script we wrote a while ago). For example, if we combine too many function calls, we may end up with a line of code that has a dozen closing brackets at its end. This is not only hard to read, but it may also lead to bugs in our code when we miss a closing bracket or include too many of them.

Note: Either of the two ways of writing code shown above is viable. However, it is often advisable to choose a middle ground, where we define interim objects whenever the code would otherwise become to convoluted.

As always, readability of the code greatly benefits from making ample use of commenting.